Diatonic Chord Substitution: A Method

When I first started studying music as an undergraduate music major I was enthralled with the idea of substituting chords. I just completely loved the sound of a major seventh chord and would use it instead of a major chord when it sounded right. At first I had no clue why it worked in certain circumstances and not in others. It was almost magical how replacing a chord could completely change the mood of a phrase from plain to bittersweet. How could adding a single note to a chord bring about a sea change of emotional content? But as my knowledge of music theory grew, so did my understanding of chord substitution. The magic turned into knowledge as enlightenment paved the way. As it turned out, it's really a simple matter of applied music theory.

How do magical journeys through mystic chords eventually turn into well-worn roads? Let me show you a way with a make-believe story about a fantastical trip through the world, with stops in several countries. Along the way we'll stop at imaginary scale and chord construction sites and enlist the aid of some precocious young music theorists with water squirt guns Have I piqued your interested? I hope so. Read on!

When traveling any unknown land, we need a good map that illustrates the terrain, roads, cities, and other points of importance. We should thank the cartographers who went before us, exploring and mapping out what they found. In music that chart is the music theory of scales and chords, to whom we may acknowledge the great work of Jean-Philippe Rameau and his seminal book, Treatise On Harmony ((Traité de l'harmonie). There were many music theorists before him (and since) who were music cartographers to whom we look for understanding.

Step One: Start with a Scale

Our route, which will bring us through the whole world of diatonic chord substitution, will start with a stop at a natural minor scale construction site. This scale can be constructed using several different techniques, one of which is described elsewhere on this website: Converting Major Scales Into Other Scales. I will use the A natural minor scale as an example because it uses no sharps or flats. You can use the same process for constructing diatonic chords using any scale.

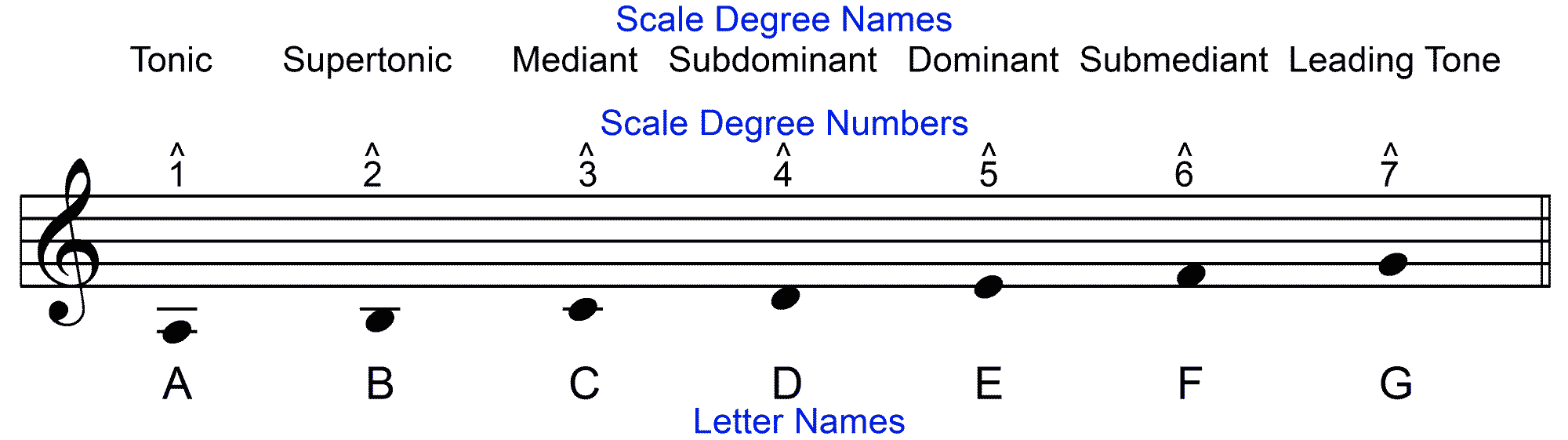

The Notes in the A Natural Minor Scale

Audio Clip of the Seven Notes of the A Natural Minor Scale

Notice that each of the seven notes of the scale has three different names: the scale degree name, scale degree number, and letter name. The scale degree numbers will be very useful in the next step, when we build diatonic triads, since they are converted to Roman numerals. Roman numerals are extremely useful for harmonic analysis, which helps elucidate the function of each chord within a given key.

Step Two: Construct Diatonic Triads

Having started our journey with a first stop at the natural minor scale, you might think we've pulled over at a less-than-exciting destination. The natural minor scale is probably one of the blandest scales used in Western music, though paradoxically this characteristic can result in profound depth. Hoping to hear more exciting soundscapes, let's get back on the road to a construction site where we'll build the diatonic triads of natural minor. Our construction engineers use a simple process that adds two sets of thirds above each note of the scale. The workers are following blueprints that tell them to use only natural notes in this case (there are no sharps or flats in the key of a natural minor), which drawn from the scale itself. (Click the play arrow to watch the movie.)

Video: How Triads Are Constructed

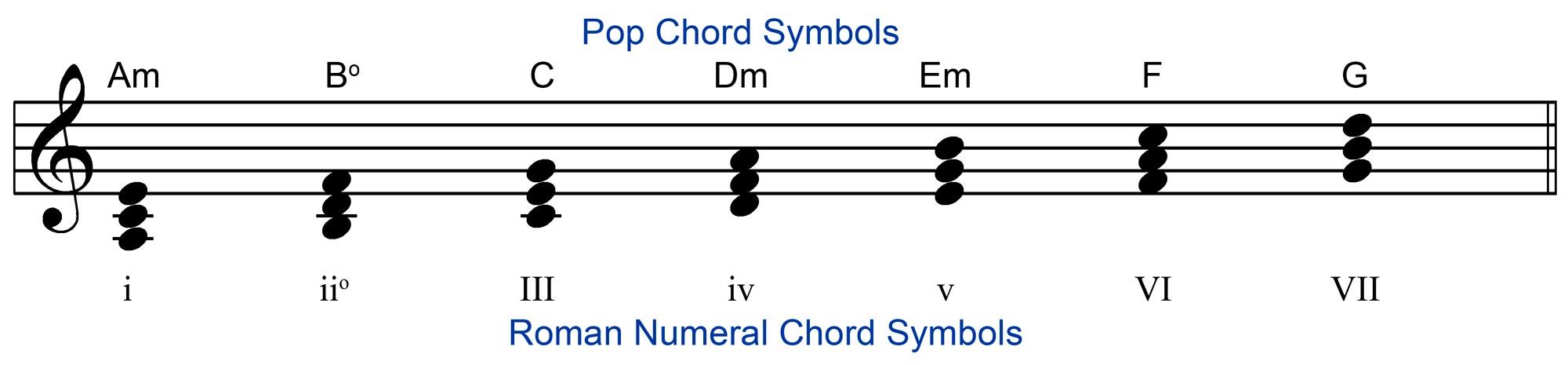

Using the same technique as illustrated in the video above, we can construct the diatonic triads for each scale degree in the key of A natural minor. Notice that all of the notes used in these chords are derived from the A natural minor scale. This is what the term diatonic means: using only notes from the scale.

The Diatonic Chords in A Natural Minor

Audio Clip of the Diatonic Chords in the A Natural Minor Scale

For more information about pop chord and Roman numeral chord symbols click on the following:

Step Three: Assemble Diatonic Seventh Chords

Having solved the problem of constructing diatonic triads using the seven notes of the A natural minor scale, what's next? Our next visit, the third leg of our trip through the map of music theory, will be to build diatonic seventh chords. How do we go about creating these chords? It's easy: We just add another third above the triads created in step two above. Here's a little video that will 'xplain it to you. ;-) I've enlisted the help of a couple of young music theorists with water squirt guns to do the work for us.

Video: How Seventh Chords Are Constructed

Step Four: Build Diatonic 9th, 11th, and 13th Chords

Weren't those girl and boy music theorists great in the previous video? (If you didn't check it out yet, you should!) I've decided to adopt them and take them on the fourth part of our journey. They're excited to use their squirt guns to create diatonic 9th, 11th, and 13th chords at the next construction site.

If you've been following this article closely, you've probably noticed a pattern: triads were built in thirds and seventh chords were assembled by adding thirds to the top. You don't suppose that we create 9th, 11th, and 13th chords the same way, do you? If you exclaimed, "yes!", then you got it! Our theorists are ready to show their stuff in the next video.

Video: Constructing 9th, 11th, and 13th Chords

Step Five: Suspended (sus) and Added (add) Chords

We're on the last leg of our world-wide journey to scale and chord construction sites. Isn't that exciting? Soon we'll be able to put together a list of all of the diatonic chords for a given scale, which will serve as a master list for substitution purposes. After all, this has been our goal all along: determine the diatonic chords for a given key/scale so that we can substitute one for another. Music campers, we've almost completed the whole tour! :-)

Besides building chords in thirds, which is the traditional way, we can add notes that sound good. These are usually at the interval of a second, fourth, sixth, or ninth from the root of a given chord. These notes are called either suspended or added notes, abbreviated sus or add, depending on the interval.

Suspension is a traditional concept that goes back hundreds of years. It historically involved a three-step process - 1) preparation, 2) suspension, and 3) resolution - which resulted in a sequence of three distinct harmonic steps. Take a look at the following video for an explanation of suspensions.

Video: Suspensions

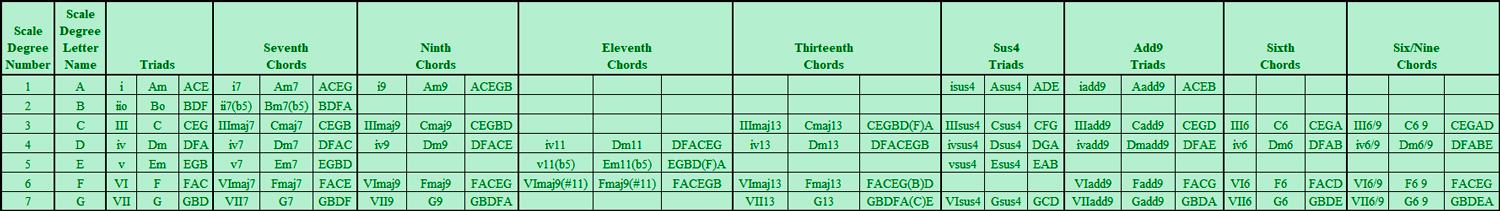

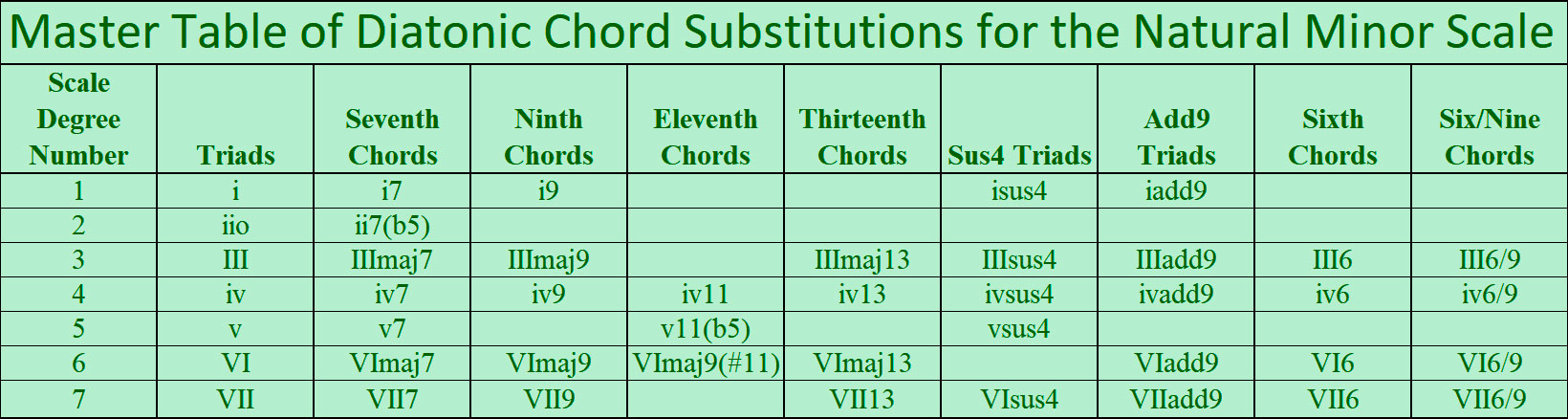

Step Six: Create a Master Diatonic Chord Substitution Table

Wow! We've done a tremendous amount of work to get to this point. But all of the heavy lifting is done and now it's like letting butter slide down a hot plate. Compile all of the chords we've found using the above steps. Here is the master chord substitution list for music that uses the natural minor scale. (It's a large table that looks small on a computer/tablet/phone, so you can download the table in Excel format below and resize it to your needs.) NOTE:

- Some chords sound awful in most contexts (except for atonal extraterrestrial screaming death metal music perhaps) so I left them out.

- You can combine chords on this list to create additional ones. For example, you could meld the sus4 and dominant seventh chords (major triad with a 7 suffix) to create a 7sus4 chord.

- I added minor sixth and six/nine chords.

click here to download this table in Excel spreadsheet format

Here is a larger, though abbreviated, version of the table.

click here to download this table in Excel spreadsheet format

click here to download this table in PDF format

Step Seven: How to Use This Table

To use this table in the key of A natural minor, simply find a chord in the list and substitute any chord from the same row. To use it in other keys, transpose it.

Step Eight: Use What You've Learned in This Article to Create More Master Tables Using Other Scales

Everything that's been discussed in this article can be used with other scales, following the steps given above. If you've understood everything, you've got a great skill set! So pick a scale other than natural minor, follow the steps, and create your own master diatonic chord substitution table.

Final Comments

Writing this article, and creating the videos and graphics, has taken an enormous amount of time. Because of this, I probably made some mistakes along the way. Please let me know if you see something that should be corrected.

I've only touched on one strand - diatonic alterations - of a much bigger rope, shall we say, of chord substitution. There are a lot more ways to come up with substitutes for chords. I wish I had the time to go through them all, but I've exhausted myself just exploring diatonic chord substitution. I hope you find helpful what I've attempted to explain in this article.

Happy Chord Substituting!

Sincerely,

Jeff Anvinson, owner/operator/music professional

JLA Music

Website and most graphics are created inhouse by Jeff Anvinson, Owner/Operator of JLA Music

Some graphics are purchased from Can Stock Photo, used by permission, and are Copyright

© Can Stock Photo

JLA Music takes care not to infringe on anyone's rights. Please contact us at jla@jlamusic.com if you have questions.

Copyright 2025 © Jeff Anvinson, JLA Music