Fully Diminished Seventh Chords

To me, fully diminished seventh chords are like flies that come and go at rare intervals. They show up for a few seconds, just to annoy you, then, just as quickly, they're gone. These chords are relatively rare in many genres of music, like Pop, Rock, Country, Blues, and Bluegrass, but they are more common in jazz. (In music there are always exceptions! Some songs may use more of them than others.) In the paragraphs that follow, I will explain what a fully diminished seventh chord is and how to construct one.

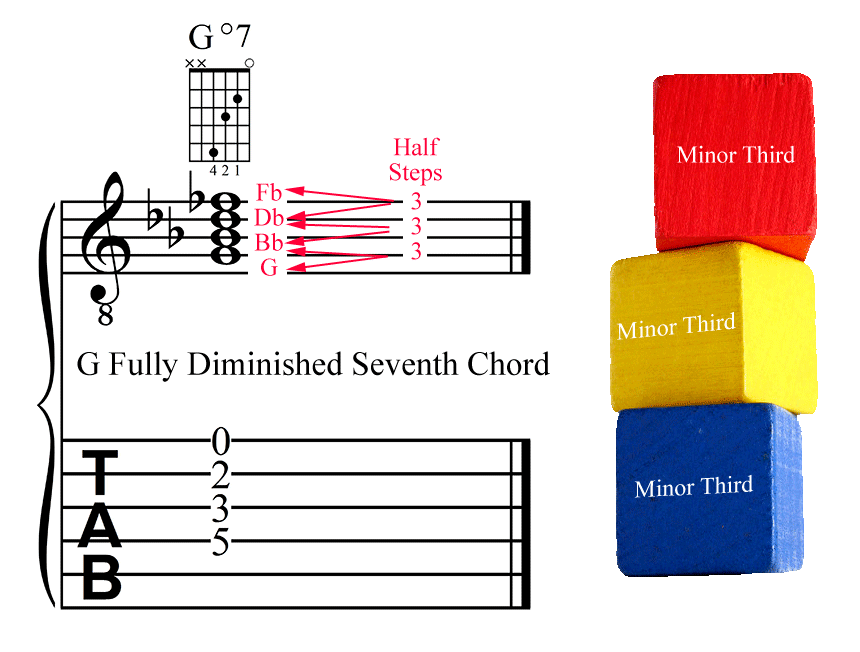

In another article on this website I explain how a cousin of fully diminished seventh chords - the half diminished seventh chord - works. You can find that article by clicking here. Fully diminished seventh chords are easier to construct than half diminished ones because they are perfectly symmetrical: They are constructed entirely of minor thirds. (If you don't know what a minor third is - read on!)

In music, there are a handful of symmetrical chords - those built using the exact same size of building blocks. The augmented triad is symmetrical, built as it is out of blocks equal to four half steps.

F Augmented Triad with an Extra Root Added an Octave Higher

I like symmetrical chords because they are nice neat packages, like square boxes. However, because the spelling conventions in music are often confusing, symmetrical chords can be problematic: The spelling of an identical-sounding chord (an enharmonic chord) changes if the function of the chord is altered. Because of these spelling rules, a single fully diminished seventh chord can be spelled at least four different ways. Notice in the example below how the chords all sound the same, and are fingered the same on a guitar, yet they are spelled differently. (OK - I think I've probably used up your patience for the minutia of music theory. Let's get on with creating some fully diminished seventh chord monsters - or should I say flies?!)

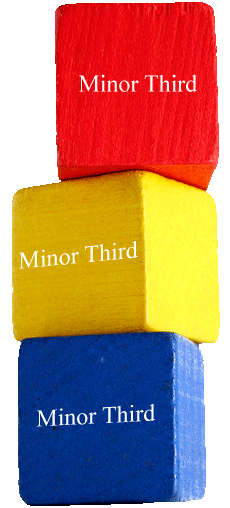

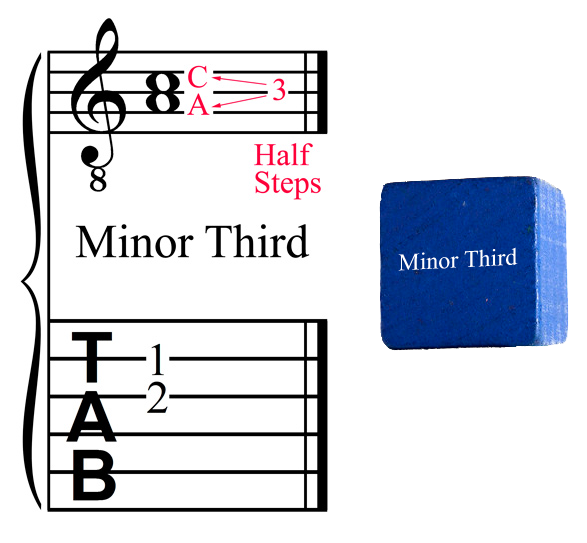

Let's start with the construction of fully diminished seventh chords by pretending we're in grade school, on recess, and playing with perfectly square boxes. These aren't just ordinary boxes - they are music boxes that are built using notes a third apart (the first and third of three alphabetically-ordered letter names) and exactly three half steps apart - like the distance from A up to C. Music theorists call these intervals (the distance between two notes) minor thirds. A minor third looks and sounds like this:

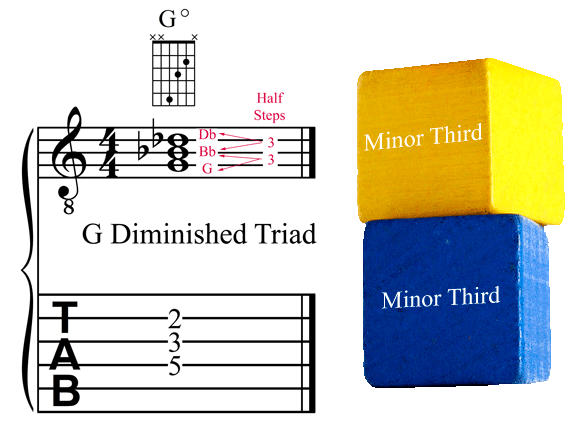

As we play in the playground we start by stacking two minor third boxes on top of each other. Yay! We've just built a diminished triad! (Click here for more about triads.) Notice that we've spelled the notes in a triad using every other letter name - the normal spelling convention for triads. It would be incorrect to spell it G, Bb, C#, because it doesn't use every-other-letter-name alphabetical order. It would sound the same (enharmonic) but it would look wrong to trained musicians. It is like spelling the word "their" as "they're" or "thayr". Spelling - unlike size - does matter!

We just learned that a triad uses two of these minor third boxes. A fully diminished seventh chord uses one more box. In our magic music playground we add one more box and we have it - a chord built of three minor third boxes. This is the fully diminished seventh chord. Again notice that it is spelled using the every-other-letter-name convention. (By the way, if you listen to how it sounds using the audio player located below the following example and exclaim, "Yikes! It's that chord they use in silent movies when something bad is happening!", you recognize the tense and unstable sound of a fully diminished seventh chord!)

Having successfully constructed a fully diminished seventh chord, we are almost done with this music theory journey into the heart of musical darkness. (Apologies to Joseph Conrad.) We only have two things to clarify.

The first issue is to review how these chords are spelled, which can be thorny in practice - though the basic rule is simple: Always use letter names that are a third apart - in other words, use every other letter name. For example, if the root is G (the root is the note that a chord is built upon), and you have used minor thirds, you must spell the rest of the chord with a B (a third above G), a D (a third above B) and an F (a third above D). Using the required distance of three half steps, the only way to spell a G fully diminished seventh chord is G, Bb, Db, Fb.

This spelling convention is why we need notes like B sharp, C flat, E sharp, F flat, and, in certain cases, double flats and double sharps. Hopefully now it will make sense why there are four different spellings in the second example from the top, all for the exact same sounding chord. For any given fully diminished seventh chord, we can spell it at least four ways - even more in certain circumstances. (These chords really are as pesky as flies!)

The second point of clarification is regarding the name of this monstrous chord. You might be wondering why it is called a fully diminished seventh chord. After all, it is built using stacks of minor thirds. Shouldn't it be called some kind of triple minor chord instead? You would think so, but some things in music theory seemed convoluted until you analyze things a bit.

We need to think of half and fully diminished seventh chords as if they are built of only two parts: the triad part and the seventh part. This is the key to unlocking their names.

The bottom three notes of a fully diminished seventh chord is a chord in itself: the diminished triad, one of the four basic triad types. We built this triad a few paragraphs earlier (or click here for a review of this triad concept.) We might say that one part of a fully diminished seventh chord is a triad. This is why it is called a diminished chord.

The word "seventh" in the name "fully diminished seventh chord" comes from measuring the distance from the bottom note to the top note. Despite the fact that we use every other letter name when spelling the chord - G, Bb, Db, Fb - the total actual distance from the bottom note to the top one in the musical alphabet is seven notes inclusive. Count with me - G (1), A (2), B (3), C (4), D (5), E (6), F (7). This solves the mystery of where we get the word "seventh" in the chord.

But you might ask, and rightfully so, what's with this use of the phrase "fully diminished" in the name? The answer comes in two parts.

First, it is because of the way that music theorists name intervals. If we counted the number of half steps from G up to Fb we get nine. (Half steps are the smallest distance in music, from one fret to the next on a guitar, or the distance between consecutive keys on a piano.) In music theory terminology, this distance - the distance spanning seven letter names and nine half steps (we must use both letter names and half steps to accurately measure distances in music) - is called a "diminished seventh".

Second, the final piece of the puzzle of the name of this chord fits when you realize that this chord has one part called a diminished triad, plus a second part called a diminished seventh. This results in both parts being diminished, hence the term "fully diminished". This is in contrast to the phrase "half diminished", which is reserved for the minor seventh flat five chord . (The minor seventh flat five chord is also called the "half diminished seventh chord" as we discovered in this web article.) This latter chord contains one part diminished triad and one part minor seventh - only one of its two parts is diminished, hence the phrase "half diminished".

I am hoping that the following example will clarify this concept.

Put another way, the fully diminished seventh chord has two parts called diminished, making it fully diminished, while the minor seventh flat five chord (sometimes called the half diminished seventh chord as explained here) has only one part that is diminished.

If you are still confused about all of these naming conventions, at least you made it this far! It might make you feel better to know that even music majors have difficulties fully understanding this concept in music theory classes. In a way, you might say that this concept is sometimes only half understood, but when you get it, you fully comprehend. (Pardon the puns.) To be honest, it is probably not that important if you don't completely understand all of this spelling and naming business as long as you understand how a fully diminished seventh chord is constructed: three minor seventh boxes piled one on top of another. Now, go to your music playground and play with minor third blocks! ;-)

In a future companion web article I will discuss the best strategies for improvising over fully diminished seventh chords. When that article is posted, I'll provide a link to it here.

Happy Music Making!

Jeff Anvinson, owner/operator of JLA Music

Website and most graphics are created inhouse by Jeff Anvinson, Owner/Operator of JLA Music

Some graphics are purchased from Can Stock Photo, used by permission, and are Copyright

© Can Stock Photo

JLA Music takes care not to infringe on anyone's rights. Please contact us at jla@jlamusic.com if you have questions.

Copyright 2025 © Jeff Anvinson, JLA Music